Newsletter Subscribe

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

Imagine this scenario: You’ve decided to take up extreme unicycle riding. It seemed like a brilliant idea at the time—great cardio, excellent conversation starter, and only a mild risk of public humiliation. But then, gravity does what gravity does best, and you take a tumble.

Next thing you know, you’re in a hospital bed, a bit groggy, perhaps with a cast on your arm and a mild concussion that makes remembering your own middle name a fun challenge.

You need to pay the electric bill. Or maybe you just want to cancel that impending Amazon delivery of 50 pounds of unicycle wax. You reach for your smartphone with your good hand. You hold it up to your face for the biometric unlock. But because of the bandages (or just the general “I fell off a unicycle” swelling), your phone looks at you, decides you are a stranger, and stays stubbornly locked.

“No problem,” you think. “I’ll just tell my daughter the passcode.” But thanks to the pain medication, the only numbers floating in your head are the lyrics to “867-5309.”

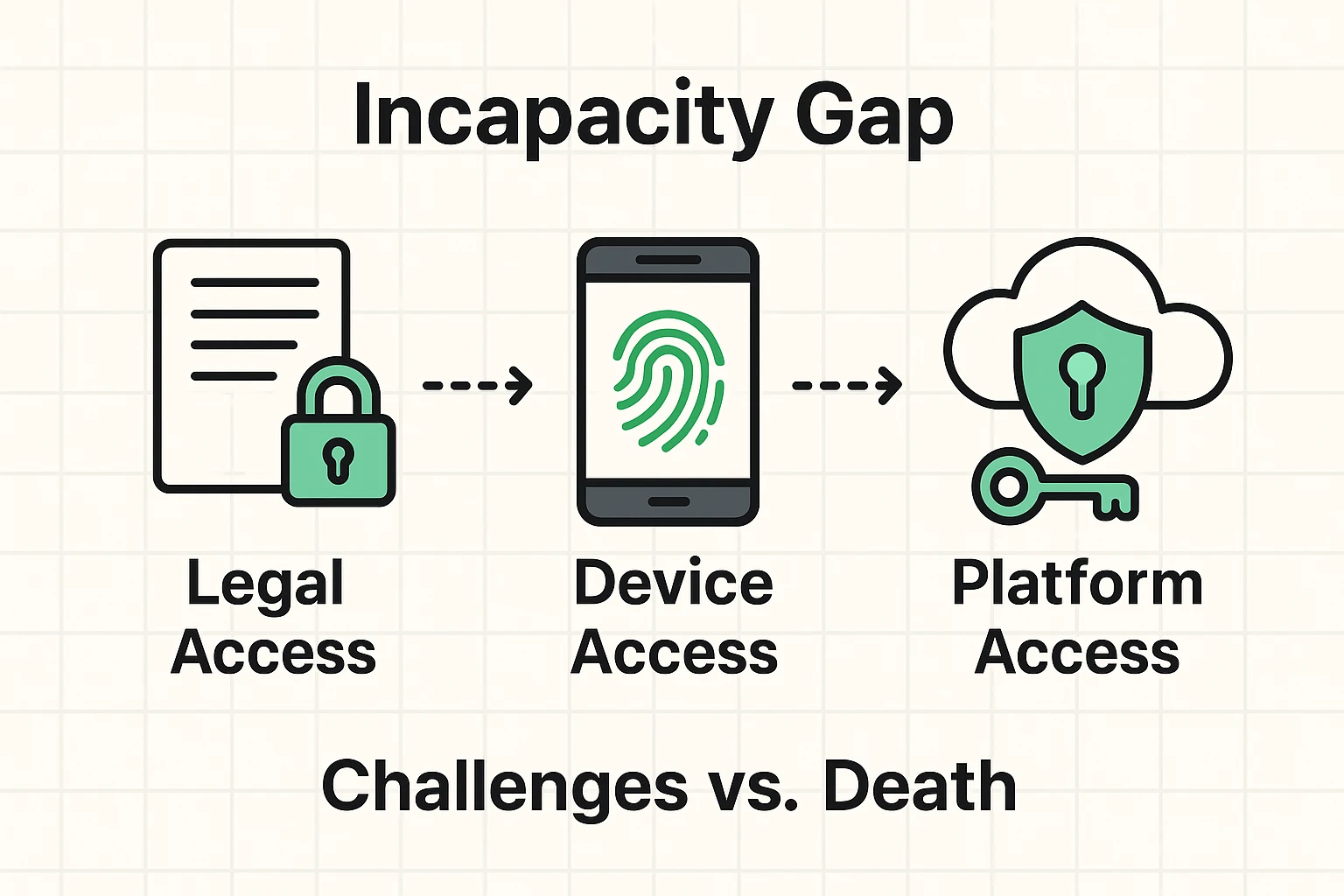

Welcome to the “Incapacity Gap.” It’s that murky, frustrating gray area where you are very much alive, but legally and technologically locked out of your own digital life.

Most of us have a plan for what happens to our stuff when we kick the bucket. But very few of us have a plan for when we just… kick the unicycle.

Here is the harsh reality that legal websites love to complicate and tech companies love to ignore: The internetThe Internet is a vast network of computers and other electronic devices connected globally, allowin... More is designed for one user. You.

When you are healthy, this is great for security. FaceID, two-factor authentication (2FA2FA, or Two-Factor Authentication, is a security measure that uses two different types of proof to v... More), and fingerprints keep the bad guys out. But if you get sick, have a stroke, or suffer cognitive decline, those same security walls keep your loved ones out, too.

We tend to think of “Digital Legacy” as something that happens after a funeral. But a huge number of seniors face situations where they are physically or mentally unable to manage their accounts while they are still here.

When this happens, your family enters a nightmare scenario. They can’t pay your mortgage online because they don’t know the passwordA password is a string of characters used to verify the identity of a user during the authentication... More. They can’t access your medical portal to see your test results because the 2FA code is going to a phone they can’t unlock. They can’t even cancel your subscription to Cat Fancy magazine.

To prevent your digital life from becoming a digital prison, you need to solve three problems simultaneously. If you miss one, the whole system fails.

You might think, “I have a Power of Attorney (POA)! My spouse can do whatever they want!”

Not necessarily.

Standard Power of Attorney documents allow someone to sign checks or sell your car. But thanks to strict privacy laws (and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act), a standard POA doesn’t automatically give someone the right to log into your email or access your cloud"The cloud" refers to storage and services that are accessed over the internet instead of being stor... More photos.

To fix this, your estate plan needs specific language referring to the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (RUFADAA). It sounds like a spell from Harry Potter, but it’s actually the law that tells GoogleGoogle is a multinational technology company known for its internet-related products and services, i... More and Facebook, “Yes, this person is allowed to touch my stuff.”

This is the one that catches everyone off guard. We rely so much on our faces and fingerprints that we forget the passcode.

If you are incapacitated, your face might change (swelling, medical equipment). Or, you simply might be asleep. (Note: Using FaceID on an unconscious person usually doesn’t work because most phones require your eyes to be open and looking at the screen. Plus, it’s creepy).

If your caregiver cannot get past the lock screen of your smartphone, they cannot get to your emailEmail, or electronic mail, is a digital communication tool that allows users to send and receive mes... More. If they can’t get to your email, they can’t reset any other passwords. The phone is the key to the kingdom.

Let’s say your daughter has your bank password. Great! She types it in.

The bank says: “We don’t recognize this computer. We just sent a 6-digit code to Dad’s phone.”

The phone that is locked in your pocket.

See the problem? Security measures designed to stop hackers also stop helpers.

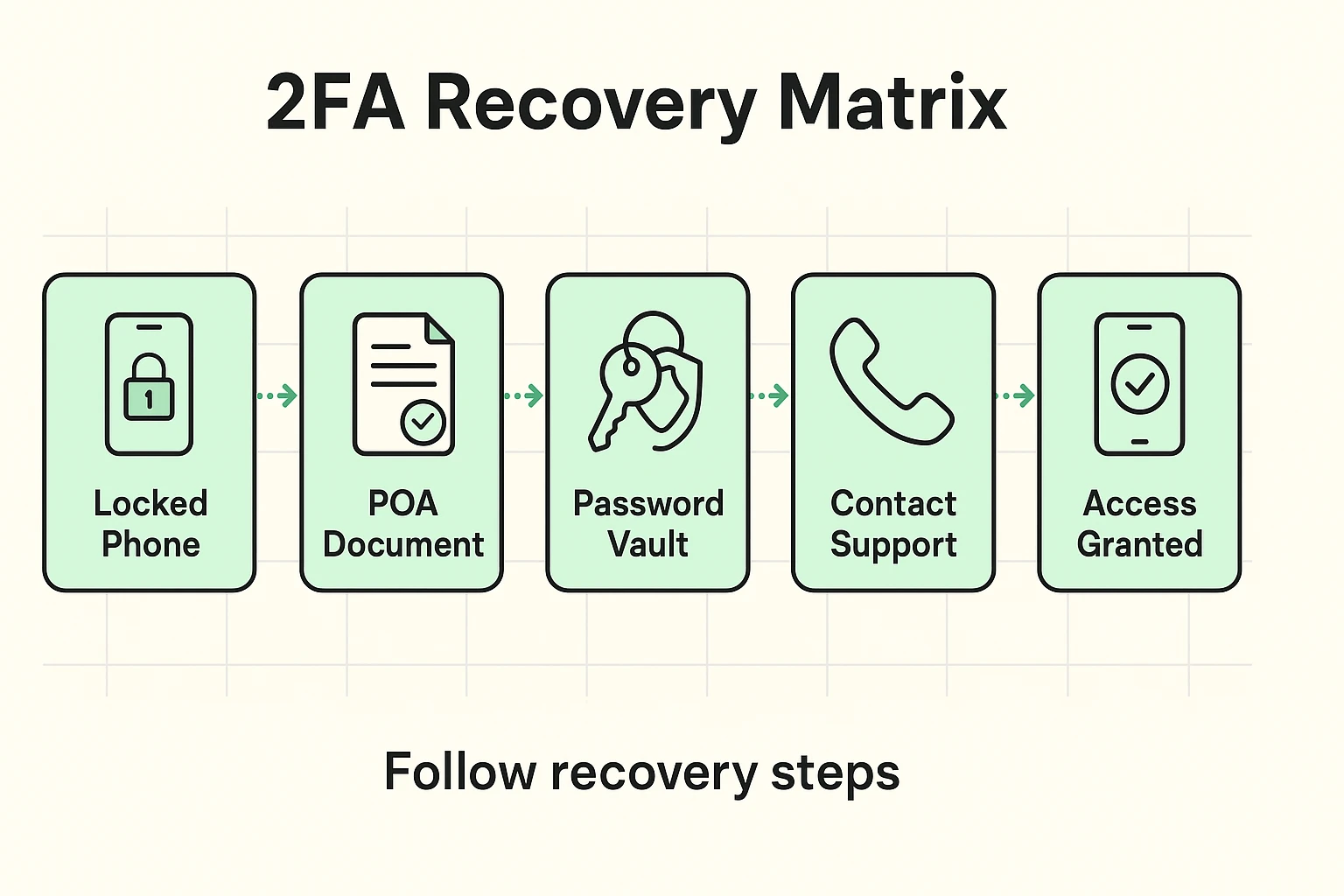

Since Apple, Google, and Meta don’t really have a “Senior is Sick” button, you have to build your own system. We call this the Technical Power of Attorney Protocol.

Here is how you set up a trusted loved one (a “Shadow User”) to step in when you can’t step up.

If you aren’t using a password manager yet, this is your sign. Tools like Bitwarden or 1Password allow you to store all your logins in one secure vault.

But here is the magic trick: These services have an “Emergency Access” feature. You can designate a contact (like your spouse). If they request access, and you don’t deny it within a set time (say, 48 hours), they get the keys to the vault. It’s a digital spare key that only works when you aren’t home.

You must write down the passcode to your smartphone and your computer. Do not text it. Do not email it.

Write it on a piece of paper. Put that paper in a sealed envelope. Put that envelope in a fireproof box or give it to your attorney.

Your caregiver must be able to unlock your physical phone. Without that, they are fighting a losing battle against Silicon Valley security teams.

Take twenty minutes to look at your digital life. What bills are on autopay? Where are the family photos stored?

Create a “In Case of Medical Emergency” document. It doesn’t need to be fancy. It just needs to say:

The big tech companies are slowly realizing that their users are human beings who occasionally get sick. But their tools are still a bit clunky.

Apple has a “Legacy Contact” feature. However, this is strictly for after death. It requires a death certificate to unlock. It won’t help if you are in a coma.

Google has the “Inactive Account Manager.” You can tell Google, “If I don’t log in for 3 months, send my data to my son.” This is better, but 3 months is a long time to wait if bills are due next week.

This is why the manual “Shadow User” setup described above is vital. You cannot rely on the platforms to save you.

This is the part where we have to be a little serious. Technically, sharing passwords can violate the “Terms of Service” of many websites. And logging into someone else’s account without authorization can violate federal law (the CFAA mentioned earlier).

This is why Step 1 (The Legal Hurdle) is so important. You want your caregiver to have legal documentation (the POA with RUFADAA language) that says they are acting as you.

It effectively tells the law: “When my daughter logs in to pay the mortgage, she isn’t hacking me. She is Me.”

You can, but it’s a terrible idea. Wills become public records after you die. That means anyone could potentially go to the courthouse and read your passwords. Plus, Wills are for after you die. They have zero legal power while you are just sick in the hospital.

Generally, no. Modern iPhones with FaceID require “Attention Awareness”—meaning your eyes must be open and looking at the phone. This is a safety feature to prevent exactly this scenario (or police trying to force unlock it).

“Hey Siri, read my emails.” This might work for basic tasks, but for anything secure (like banking or health data), the device will usually ask for a fingerprint or passcode before proceeding.

Thinking about incapacity isn’t fun. It ranks right up there with root canals and listening to someone describe their dream in detail.

But taking an afternoon to set up a “Shadow User” plan isn’t about being morbid. It’s about love. It’s about making sure that if you ever do take a tumble off that unicycle, your family can focus on holding your hand and helping you heal, rather than screaming at a customer service robot because they can’t pay the electric bill.

Take the time. Write down the code. Clean up the digital mess. Your future self (and your family) will thank you.